Fanny's Fact Check: How do we communicate with people from the future?

If we safely store our radioactive waste underground, how do we ensure that someone doesn't accidentally come into contact with that waste 100,000 years down the road? How will they even know what exactly is under the ground? The latest edition of the Kiekeboes comic strip, "Uranium-235", touches on a major challenge in the long-term management of radioactive waste.

© In association with De Standaard Uitgeverij. All prints and storylines belong to them.

Currently, the general consensus is for deep or geological disposal to safely manage high-level radioactive waste. This means that the waste is stored deep underground for hundreds of thousands of years. Safely isolated from humans and the environment, in rock or clay layers. Read more about high-level radioactive waste on the other Kiekeboe page.

Read more about high-level radioactive waste in Fact Check #5:

Do we store our radioactive waste 400 meters underground?

In this fact check, we explore the issue of nuclear memory. How do we warn the people of the future? In Belgium, ONDRAF/NIRAS, the National Agency for Radioactive Waste and Enriched Fissile Materials, is responsible for waste management, and therefore for preserving knowledge and memory about this waste. Important steps are already being taken today in Belgium to preserve the nuclear memory of radioactive waste.

One example is Tabloo, the visitor and communication centre built by ONDRAF/NIRAS in Dessel in cooperation with the local community and the partnerships MONA and STORA. But the challenge of preserving this knowledge for 100,000s of years is complex, and there is still a lot to be researched and decisions to be made. That's why many scientists are looking into this problem around the world, including our social scientists at the SCK CEN research centre.

Fun fact! This fact check looks into the best way to communicate with people in the future. But you could also go completely the other way, and decide not to communicate anything at all, trying to erase all memories. Close everything off completely and forget about it. If it's forgotten, future generations have no reason to dig there. Just look at the pyramids, which have prompted people to dig ever deeper, that wasn't the intention of the Egyptian builders either.

Time & language

"æt þearfe man sċeal frēonda cunnian". Chances are slim that you'll immediately understand what is written here. But this is actually English. Or at least the English of the 11th century. Today we would write this as "A friend in need is a friend indeed''.

In other words, language changes, and quickly. After 1,000 years, it is barely intelligible. So what language should we use to warn our distant descendants about radioactive waste? Simply relying on language is not enough, scientists already agree on that. So we have to look for other solutions, such as using drawings and illustrations.

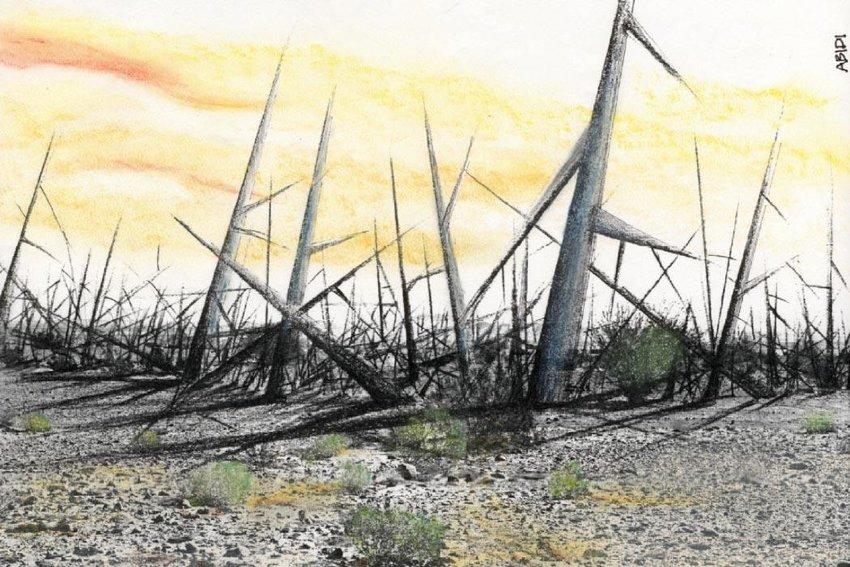

Fact: In the 1990s, several teams of American scientists and artists worked on long-term communication plans for a radioactive waste repository in New Mexico. Some of them especially wanted to highlight the potential dangers of this disposal site. One proposal was to add artwork or structures on the site itself to warn people of the potential danger, such as large pegs rising from the ground to deter future generations.

Perishable materials

When we think of storing information, we tend to think that the information we store today will be passed down unchanged to people in the (distant) future.

Time capsules are a typical example: today, old crates or boxes containing letters, small objects or postcards are regularly found, which our ancestors deliberately buried to give a snapshot of life in their day. The question, of course, is whether the information will still be readable and understandable when the capsule is opened after thousands of years.

An example? Take a floppy disk, most people know it only as an icon to save a file on your computer. But decades ago, this was the standard way to store data. Try finding a computer today that can still read a floppy disk....

So it's not just a question of choosing language or drawings. The material also needs to stand the test of time.

Fact: There is also a kind of time capsule on board the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft, which face more or less the same challenges. 'The Golden Record' on board is a gold-plated copper disc, similar to a gramophone record. The disc contains sounds and images, including greetings in 55 languages. The ambitious goal was to send a universal message to potential aliens. An ambition similar in many respects to passing down information to our descendants in 100,000s of years' time...

Actively passing on information

We can overcome the problem of language and data carriers becoming obsolete by continuously adapting information to new languages, or transferring it to new data carriers. This requires active input from people in the future. How can we guarantee this?

There is no one concrete solution. An important consideration though is that culture plays an important role in keeping a message alive. And how can you embed something in a culture? That's right, through art, stories, religion, rituals, etc.

Ideas have already been proposed, such as ...

-

Atomic Priesthood

One thought-provoking, if unrealistic, example is Thomas Sebeo's idea of creating an "Atomic Priesthood": an order of priests at the disposal site who are responsible for passing on knowledge. The success of such an initiative would primarily depend on creating rituals and traditions that ensure people are deterred from entering a disposal site. This idea was never intended as a concrete recommendation, but gives a good idea of how important and difficult it is to anchor something into a culture.

-

The Ray Cat Solution

An even more eccentric idea was put forward by two philosophers, Françoise Bastide and Paolo Fabbri. They wanted to breed radiating cats, which change colour any time they come near radioactive material. Like with the atomic priesthood, they wanted to create legends and myths that would survive through poems, paintings and music. The message: "If you see a cat change colour, get out of here!"

What information should we preserve?

Suppose we found the ideal solution to pass on information, to speak to the people of the future. That leaves us with the challenge of deciding what information to preserve.

In the future, will people need to know exactly where our radioactive waste is disposed? And what waste it is? And then what if someone has malign intentions?

Should we just preserve everything we know about radioactive waste management? Is that even possible, given the sheer volume of all the reports, scientific publications, policy documents, and other information we have already produced (and in some cases already lost)? Or is it better to focus on more general information?

The best approach is probably to preserve different information for different target audiences. More detailed descriptions for responsible actors in the shorter term, more general messages for people in the more distant future.

Conclusion

Preserving information about radioactive waste is therefore a lot more complex than you might think at first glance. The illustrations in the Kiekeboes comic are not enough then! Linguists, anthropologists, sociologists, archaeologists, policy makers, as well as artists and writers, have therefore been thinking for decades about how to meet this challenge.

These days, the general consensus among international experts is that different ways should be used to preserve information about radioactive waste for the future.

Two ways

-

This involves using time capsules, works of art, or above-ground and underground markings of disposal sites.

-

This is a more active form of communication whereby messages and data carriers are passed from one generation to another, for example through museums, archives, education and cultural activities.

Experts also advocate preserving different types of information, for different audiences. These would range from broadly general messages to detailed descriptions of the radioactive waste and how it was disposed of. Important information in the "Key Information File (KIF)" is in fact best preserved in different places.

Using different and overlapping sources of information makes it more likely that some messages will be passed down over the longer term. Then it wouldn't matter as much if one or several of the initiatives were to disappear over time. But ultimately, of course, only time will tell if the different methods worked out as expected, or not.

If you want to read more about this integrated approach, you can find more information in a report by the OECD NEA (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, Nuclear Energy Agency):